Part way through writing this week’s chapter of our anthology on teacher stress, I came across a post on the Derby University blog that expressed all I had in mind – except with more insight and erudition than I can quite manage. So with their permission, we have a guest post from Dr Sarah Charles and Dr Alison Hardman, Senior Education Lecturers at the University of Derby, discussing the role of a ‘teacher’, reasons for sick leave within the profession and how the ‘stress epidemic’ can be tackled. If you agree with the thoughts of the two doctors, don’t forget to share and spread the word!

Teaching: A Burnt Out Profession?

The negative rhetoric surrounding the teaching profession continues. Headlines warning of a crisis within the UK education system have long dominated the press and social media. These headlines have conveyed stark and worrying messages about all aspects of the profession from an apparent mass exodus of teachers – with the National Audit Office estimating that 35,000 teachers left the profession last year for reasons other than retirement; to an unprecedented, 43% decline in the number of applications to Initial Teacher Training programmes causing us to question whether teaching is becoming a Mary Celeste profession. More recent reports state that teaching staff experience the highest stress levels and the highest number of suicides than any other profession.

Findings from recent research, commissioned by the Education Support Partnership, highlighted that 75% of 1,250 education staff questioned, reported that they had experienced psychological, physical or behavioural symptoms related to work, compared to 62% of the UK working population. Pressures of workload and a lack of work-life balance were the two top cited reasons for teacher stress, with 29% of respondents indicating that they felt stressed all of the time (compared to 18% of respondents working outside of the sector) and 45% of teachers stating that they do not have a work-life balance. The impact of this is far reaching, with nearly half of all respondents (47%) reporting that their personal relationships had suffered as a result of being in the job. Most worryingly, the Office of National Statistics reported that the suicide rate among primary school teachers, in England, between 2011-2015, was 42% higher than the wider population.

What do the statistics show?

These statistics are hardly surprising in an era which has seen unrepentant government involvement in education, and has called into question the professionalism, skills and ability of teachers to do what is best for the pupils they are teaching. The ‘standards drive’ approach to teaching/ learning, an increasingly narrow curriculum and teaching to the test, allied with the pressure of Ofsted ratings, results and performance in league tables, makes the demands of teaching a weight that many simply cannot bear.

So, what is the role of a teacher?

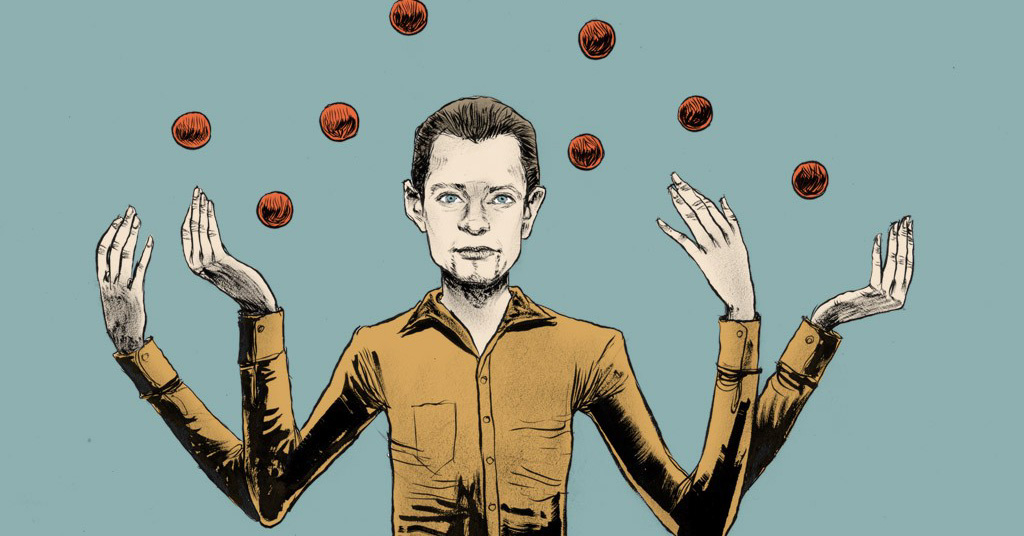

The role of the ‘teacher’ in 21st century society has changed significantly. Not only are teachers required to plan, teach and assess on a daily basis, complete swathes of paperwork at home and over the weekends, they are also now home office workers responsible for national security issues (through the rise of the PREVENT agenda); nutritionists, as a result of healthy eating initiatives; social workers identifying children at risk; and now, due to the rise of mental health awareness, they must operate as counsellors responsible for the well-being of the pupils they teach. But who will take responsibility for their wellbeing?

With teachers being repeatedly blamed for many of the ills in society, the responsibilities are huge, the stakes are high. Which other profession requires such a multiplicity of diverse and demanding roles simultaneously and relentlessly? Even when ill, 72% of teachers feel the pressure to go into school, according to The Times Educational Supplement. So why are we surprised that many teachers are on the verge of burn out?

Of course, it is important that children are at the centre of our education system but this should not be at the exclusion and detriment of the people teaching them. It should be a co-owned space where teachers’ health and wellbeing is given equal status with the children they are teaching, not at the expense of it. Remember, the text ‘Every Teacher Matters’ (2012) by Lovewell, which questions why, despite being one of the most valuable resources in education, there is limited investment in the wellbeing of teachers?

We need to seek to understand the root cause and nature of this stress. Is this the result of feelings of disenchantment, disempowerment, lack of control and unrealistic expectations that teachers are the panacea for social improvement? Is it that some new entrants into the profession are poorly prepared by their short-term, quick fix, recruitment initiatives that leave them vulnerable and exposed to the harsh reality of the classroom long term? Is it that recruitment processes are not robust enough to select those with the required resilience and tenacity required for success in 21st century classrooms? Or is it poor leadership within schools that places unprecedented and unfair expectations onto teaching staff which ultimately leads them to burn out?

What we do know is that ‘stress’ has become an all-encompassing term, synonymous with the teaching profession. However, this single term can often mask the complexity of different mental health issues. It has become a ubiquitous term that can be unhelpful and serves to denigrate genuine problems. It is a personal, contextual, situational, emotional response to circumstances often beyond one’s own control. So, how can we empower teachers to adopt creative responses to challenging circumstances, to inquire how they might improve educational approaches to teaching and learning and to instil in them a belief that they, as highly qualified professionals, actually have an active voice which is listened to and heard?

The role of leadership

To this end, leadership is key. Leaders have a responsibility to implement reforms that readdress the work-life balance of their staff, not to add to it, out of a misguided belief that behaviour such as staying on the school site until 6pm every day or taking 120+ books home every night to mark, will improve their next Ofsted rating. Such behaviours do not define teacher effectiveness nor do they guarantee pupil progress, but are a sure fire way to perpetuate stress in an already beleaguered profession.

What can be done to tackle the ‘stress epidemic’?

No one else will turn the tide of negativity which currently dominates the educational press. A moral panic around the profession has the danger of becoming a self-fulfilling prophecy which threatens to destroy it from within. We need to refocus the rhetoric and celebrate this uniquely rewarding profession and all it can afford. As a teacher, you have the potential to make a lasting difference and, in the words of the American historian Henry Adams, “A teacher affects eternity.”

We need to now seize the opportunity, as a professional learning community to attract and develop the next generation of critical thinking teachers who thrive on the challenges of teaching, who enjoy the spirit of learning and who are, ultimately, masters of their own destiny.

Thanks to the University of Derby blog for their insights – the original blog post can be found here. Don’t forget to like and share with anyone who cares about the state of education in the UK.